This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

On the 13th September 2019, Recovery in the Bin delivered their keynote talk at the 25th International Mental Health Nursing Research Conference. We are publishing the text of the talk, in full, here.

To reference this transcript, please use the following:

Recovery in the Bin, Edwards, B. M., Burgess, R., and Thomas, E. (2019, September). Neorecovery: A survivor led conceptualisation and critique [Transcript]. Keynote presented at the 25th International Mental Health Nursing Research Conference, The Royal College of Nursing, London, UK.

You can also watch the video from the conference which was live streamed:

And! After the presentation André Tomlin, The Mental Elf interviewed the RITB presenters for a podcast, we may even occasionally have made some sense!

Acknowledgments: Thank you to @jadeelizb, @RRowanOlive, & Vince Laws for artworks. @maddoggie2, Nell Aitch, Anne O’Donnell, Andi Fugard, Alan Meudell, and G, for their support, feedback and advice during the keynote’s production, performance and aftermath. And to all the survivors whose voices have contributed to this critique over the years, Thank You Binners!

We hope the term neorecovery will help professionals involved in your care understand.

And we hope we have done you proud.

Click Slide images to embiggen!

Neorecovery: A Survivor Led Conceptualisation And Critique #MHRN2019

The Voices of Lived Experience

Introduction

Recovery in the Bin is a user-led critical theorist group, who have spent half a decade at least critiquing recovery and making jokes in order to survive. We are not academics, we are ‘Binners’, and we come from beyond academia, from a mysterious place you may have read about, known as ‘Reality’. ‘Anecdotal’ is not a dirty word in our world, and our hierarchy of evidence has lived experience right at the top!

Our focus and critique is therefore based on our user-led collective’s experiences, which are grounded in the way recovery is understood, researched and implemented with people who have severe and long-term mental health conditions. We are today’s ‘grassroots’ – the very people from whom the recovery vision originally emerged.

In 2014, we began as a small Facebook support group for people who felt “abandoned by recovery”. The group was founded by three mental health survivors who remain integral to our work today.

Since then, we have grown beyond our founders’ wildest dreams! We have a twitter account, and a blog which has been referenced more than 138 times, including by some of you here today. We even have our very own spokesperson, Rita Bins, who likes to make an appearance every so often. We have listed some of our most notorious blog posts which you may want to check out later, they include our Unrecovery Star and our Stepford Recovery College Prospectus .

Unsurprisingly, we have come to speak to you today about Recovery. However, we aren’t going to repeat our familiar critique which can be found on our internationally renowned blog Today we aim to build on this critique by conceptualising and describing what we call ‘neorecovery’.

This will be the first time we have presented these ideas, therefore, please reference this presentation so we can be recognised for our original contribution to knowledge.

As this is a mental health nursing research conference, we are fairly confident that you all know about the existence of the ‘recovery’ approach, concept, notion, vision or model- please pick your preferred description -and you should know about some of its faults and flaws, trials and tribulations. So, we’ll skip the basics of recovery so we can spend more time on our critique!

Recovery’s Emergence in Policy

Recovery appeared in English mental health policy in 2001 and shortly after in the rest of the UK. It reflected Anthony’s (1993) frequently cited grassroots user-led definition, which originated from people with severe and enduring mental health conditions in the United States in the 1980’s and early 1990’s. You’re probably well versed in Anthony’s quote by now but for anyone who isn’t here it is:

Despite recovery’s prominent place in policy in 2001, little was known about what recovery orientated services would look like or the contextual barriers to implementation in the UK. And, importantly for a research conference, there was no robust UK evidence base to support its prominence in policy.

It is also extremely important to note here, and perhaps this is glaringly obvious, that Recovery’s prominence in policy in 2001 was highly political and to be more specific, neoliberal.

Neoliberalism and the Emergence of Neorecovery

We will return to the word neoliberalism multiple times in this presentation, so briefly for those of you who are not familiar with the word:

“Neo-liberalism values individual interaction in free markets. It argues for welfare state cutbacks and greater individual responsibility and stresses the importance of opportunity.

This in turn underscores particular themes in public attitudes (deservingness, obligation and choice) and downplays others (solidarity and community).”

Neoliberalism is the dominant ideology of many major governments around the world. It’s ‘holy trinity’, is deregulation, privatisation and the cutting of social provision, such as welfare and social care.

Recovery was therefore, enacted in policy and services had to implement it. However, they had little idea if or how it was possible and were perhaps unaware of its politicised nature and the potential harms that this may cause. In this context of confusion and politicisation, Neorecovery’s seedlings emerged.

‘Recovery’ in the Real World

Fast forward to the present day, the ‘Recovery Approach’ has not been an astounding success for service users.

At one time, we thought we were radical, but it seems people are catching up with us! Like recovery itself, our critical stance on recovery has become mainstream!

Eighteen years later and we are suffering the consequences of a politicised, poorly defined and understood ‘recovery’ in policy.

We still don’t have a shared understanding of what recovery means in practice or what it should look like.

It is widely acknowledged that recovery’s implementation in the real world is inconsistent and suboptimal. In fact, the REFOCUS trial suggests that a UK context poses considerable barriers to ‘recovery’s’ effective implementation.

We still do not have a robust evidence base for widespread ‘recovery’ interventions including Recovery Colleges. That’s 18 years AFTER ‘recovery’ entered policy! As the Mental Elf likes to remind us, it takes 17 years for research to enter policy, but after 18 years in policy we still don’t have the evidence we deserve as service users.

And ‘recovery’ has continued to be politicised, or as some people say, politically co-opted.

As one of our members Robert Dellar put succinctly in 2014, “Recovery has always only ever been an empty word that refers to whatever agenda or ideology anyone chooses.” Robert didn’t specifically mention neoliberalism but given his other notable survivor works, we are confident that the agenda and ideology of neoliberalism were firmly in his mind.

Neorecovery

In the context of 18 years of confusion, ‘sub-optimal implementation’ and political co-option and corruption, we propose that a new and distinct ‘recovery approach’ emerged, which has so far remained unarticulated.

We call this neorecovery.

The word “neorecovery” was coined around 2017, by a co-founder of Recovery in the Bin.

We want to make explicit for you this unarticulated and often unconscious approach that significantly influences research, practice and policy in the UK, and is now even packaged and branded for global export.

Our conceptualisation or description of neorecovery is in its infancy, however, we propose that neorecovery is distinct from the recovery vision which originated from grassroots survivors. We’ve created this table to explain what we believe are neorecovery’s key departures from the original grassroots’ recovery vision:

We hope services aren’t ALL delivering neorecovery and we hope not all interventions currently being researched and evaluated are neorecovery based.

We hope that there are informed researchers and services, where recovery is being implemented in accordance with its grassroots vision and ethos.

We recognise that there may be services where only some practices resemble neorecovery and there may be researchers and clinicians who don’t realise that they are implementing neorecovery.

We’ll now move on to describe these key departures in more detail, paying attention to the differences in Recovery and Neorecovery’s population, theory, values, beliefs, politics and power dynamics. We’ll also talk about the impact these departures have had on mental health services and people who live with severe and chronic mental health conditions – the target population of the original recovery vision – many of whom feel, and are, abandoned and excluded by neorecovery.

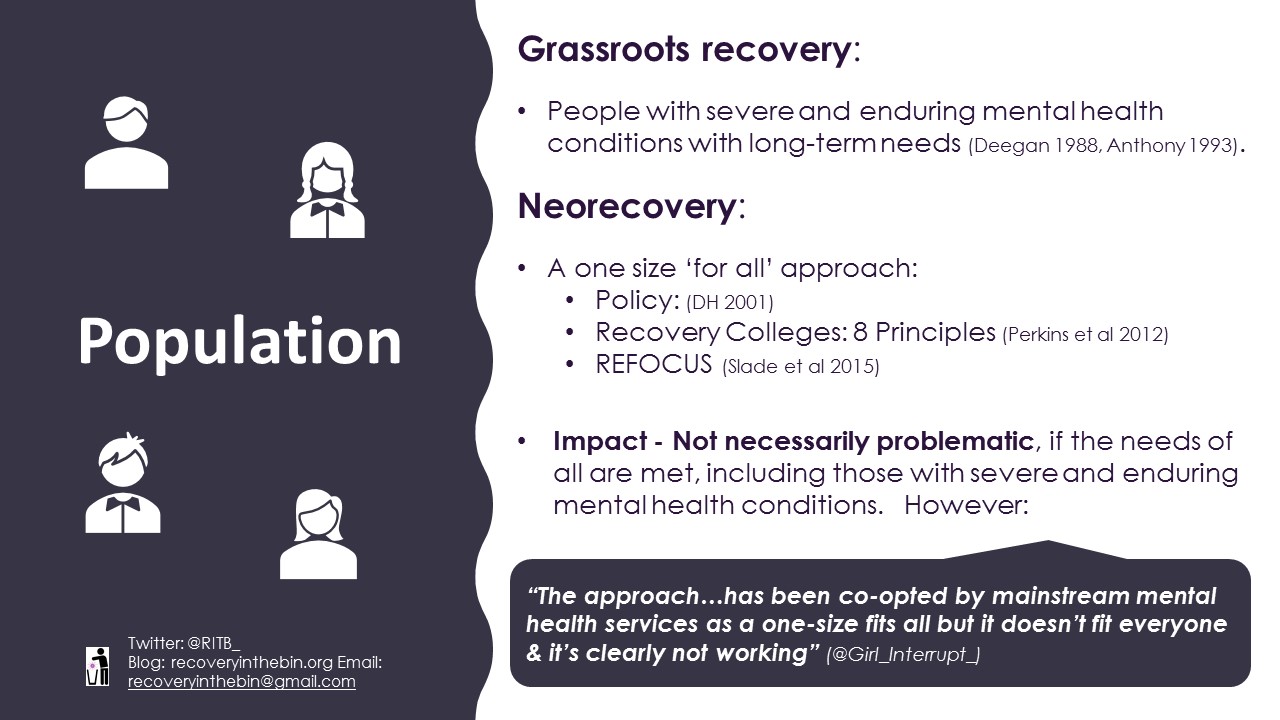

Differences in Population

It is well known that grassroots visions of ‘recovery’ were firmly rooted in the lived experience of people living with severe and enduring mental health conditions. However, neorecovery is typically applied in a blanket fashion to all people who use mental health services or experience a mental distress. We have seen this blanket application in policy and we also see this in the Eight Principles for Recovery Colleges and the REFOCUS intervention which is described as “suitable for various diagnoses and all types of community-based adult mental health teams”. Service users are also aware of this, as this quote from a service user highlights, “The approach…has been co-opted by mainstream mental health services as a one-size fits all but it doesn’t fit everyone & it’s clearly not working” (@Girl_Interrupt_)

This shift in focus is not problematic if the needs of all are met. However, combined with neorecovery’s additional departures, we argue that there has been a shift OR ‘REFOCUS’ from services and research that meet the needs of those with severe and long-term conditions, to those that meet the needs of the majority with mild, moderate and time-limited conditions.

Departure in Theory

Reflecting grassroots recovery’s grounding in the experiences of people living with severe and enduring mental health conditions, it was deeply embedded in the theories and ideas of the social model of disability, with its emphasis on the ‘total’, long-term impact of severe mental illness. This included functional disability including our ability to get our daily living activities completed, how we are treated by society, including discrimination and stigma, and the inequalities we face, for example economically and poor housing.

Neorecovery, on the other hand, is not grounded in a social model of disability. Its key proponents view disability, like symptom reduction, as a facet of ‘clinical recovery’. Neorecovery interventions, including REFOCUS, are founded on psychological theories about attitude and behaviour change, while Recovery Colleges are based on educational approaches.

It seems that recovery’s grounding in a social model of disability is something lost to history like the asylums. It’s throwing the baby out with the bathwater!

So, what’s wrong with the shift in focus? By forsaking a firm grounding in a social model of disability, and not fully acknowledging psychosocial disability, neorecovery interventions do not actively address the substantial long-term societal barriers and social disadvantages that people with mental health conditions experience day to day. Rights-based approaches that lack firm grounding in an understanding of long-term psychosocial disabilities, will, like the REFOCUS intervention, be no more effective than usual care for us.

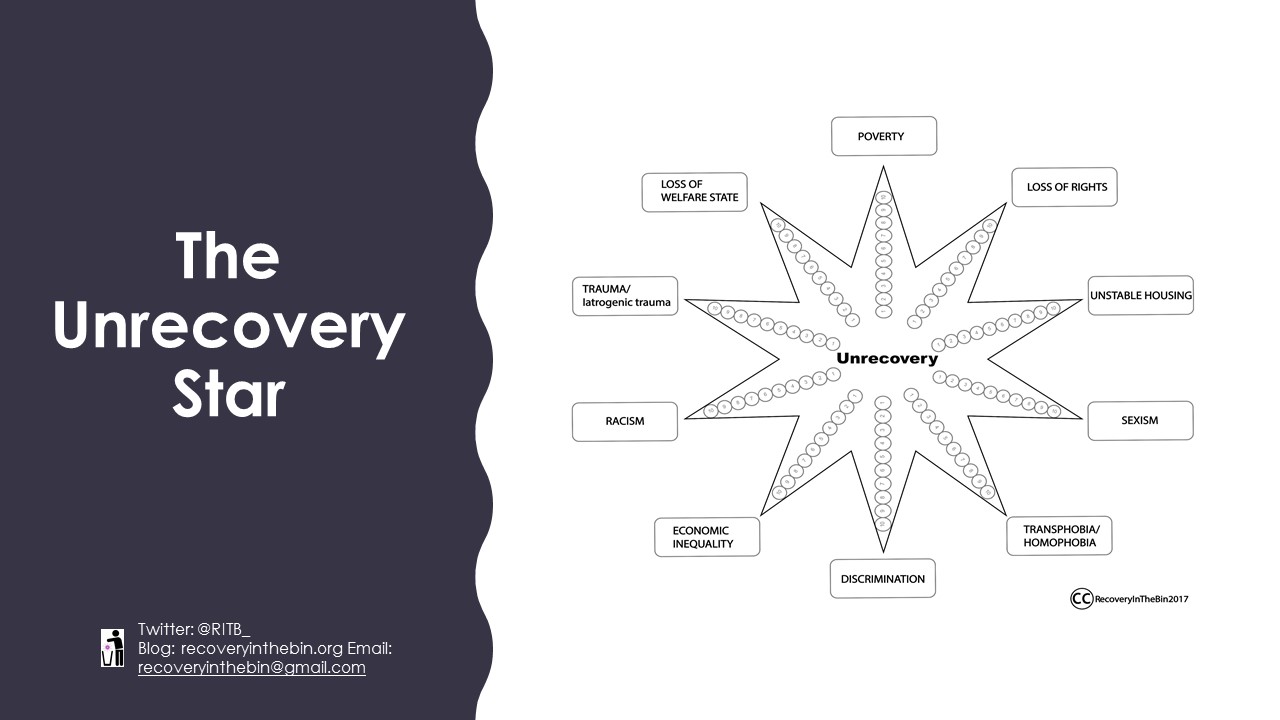

Our Unrecovery Star highlights our social reality.

So, we ask: Where are the ‘recovery’ orientated interventions, conceptual frameworks, campaigns, marches and demonstrations that address the socio-political injustices that people with enduring mental distress experience?

We acknowledge there are some initiatives, addressing this but they are far from widespread. No amount of REFOCUSSING, or re-education at Recovery Colleges will remove these injustices. Talking about the social determinants of mental health is insufficient – actions speak louder than words.

Departure in Values and Beliefs

Reflecting its grounding in a social model of disability, grassroots recovery was heavily critical of oppressive mainstream “American” values, including “rugged individualism”, competition, personal achievement, and self-sufficiency. They advocated for a wide variety of services based on alternative values such as collectivism and co-operation.

However, glancing at the heavily branded and marketised ‘recovery stories’, interventions, service innovations and transformations, it is clear that Neorecovery embodies the mainstream values of individualism. We see individualistic buzzwords everywhere, like ‘self-management’, ‘independence’ and ‘responsibility’.

What’s wrong with this departure?

As Deegan eloquently stated in 1988:

“For some psychiatrically disabled people, especially those who relapse frequently, these traditional values of competition, individual achievement, independence and self-sufficiently are oppressive. Programs that are tacitly built on these values are invitations to failure for many recovering persons. For these persons, “independent living” amounts to the loneliness of four walls in the corner of some rooming house. For these persons, “individual vocational achievement” amounts to failing one vocational program after another until they come to believe they are worthless human beings with nothing to contribute. For these persons, an alternative type of rehabilitation program, and even lifestyle, should be available as an option.”

Deegan could have been writing today. 31 years later, the oppression, failures, feelings of worthlessness and loneliness continue.

Like we said, we live in the real world. In the real world, some people may never be capable of competitive employment. Some people may always need intensive support to remain independent. Conflating ‘independence’ with self-sufficiency and then demanding chronically disabled people be self-sufficient is unethical and cruel.

Disabled activists never intended ‘independence’ to be understood as synonymous with a self-sufficient neoliberal ideal.

As Disabilities Rights UK succinctly explains: “… the essentials of independent living… the right to choose how your support needs are met, control over your day-to-day life, that you are your own expert on your life, that you should have choice in deciding how your support needs are met, and that you should be able to play a part in society.”

Words like independence, personal responsibility and choice may sound empowering and self-actualising, but in the context of neorecovery, these humanistic versions of individualism have been distorted to fit the ideals of neoliberalism. Phrases used in everyday clinical practice, like ‘reducing dependency’ and ‘taking responsibility’, now reflect government neoliberal attitudes, particularly in relation to economic efficiency, welfare reform and welfare to work.

We have developed some artwork to protest – Take your responsibility pill!

We are now blamed for our failure to recover within prescribed timescales and our inability to conform to the neoliberal ideals of self-sufficiency that are embodied in neorecovery. We are called dependent, discharged from services and re-diagnosed with personality disorders for not getting better. It is individualism at its most cruel.

The Rise of Positive Psychology

Closely connected to neoliberal individualism, and another key departure from grassroots recovery, is Neorecovery’s over emphasis on positive psychology, or as Woods and others say “compulsory positivity”.

It’s important to remember that grassroots recovery maintained that negative thoughts, emotions and experiences like anger, failure, despair, denial, anguish, were key features of the recovery process, alongside positive thoughts, emotions and experiences like hope and optimism.

In contrast, Neorecovery places positive psychology centre stage and success and positivity appear compulsory. CHIME, the most cited ‘recovery’ conceptual framework which has significantly influenced practice, neglects these essential processes in favour of hope and optimism. The REFOCUS intervention formulaically prioritises individualised, future orientated goals and seeks to assess and amplify strengths.

Little room is afforded for our real struggles, difficulties, failures and our past.

So, what’s wrong with this departure?

Optimism, inappropriately administered, was seen by grassroots proponents as a significant hinder to the recovery process – and we agree. Deegan advocated for flexible services that don’t ‘abandon’ those of us who need long-term support in our suffering. Sometimes we need time to be mad. We need support when we – like Deegan – feel anger, denial, anguish, failure and despair. But we are still abandoned for days, weeks, months and years. Far too often, we remain alone.

A quote from our co-founder @Maddoggie2 highlights the invalidation inflicted by inappropriate optimism.

“There’s no limping along recovery now… there’s celebrity recovery. There’s no room for madness anymore – people used to be actively psychotic and in emotional pain on stage at conferences…. now we must be sanitised ‘normals’. We reserve the right to be in a state of unrecovery.”

Differences in Power Dynamics

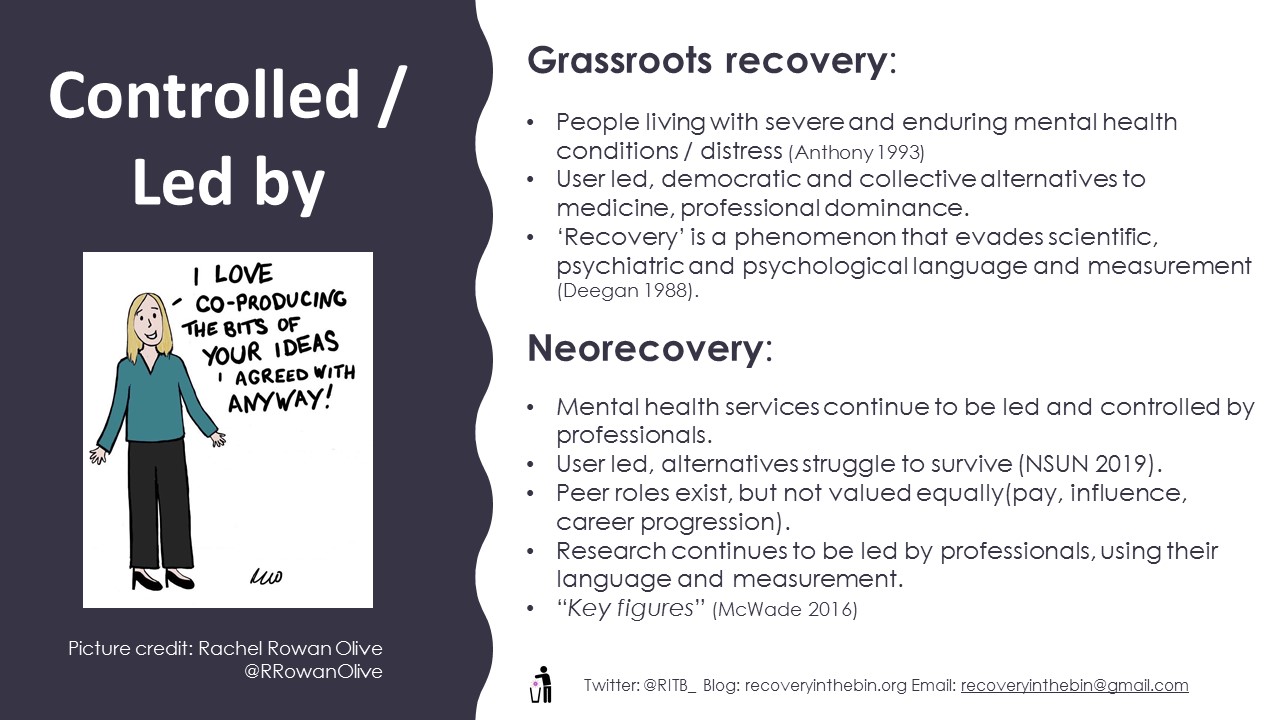

Our next proposed key departure centres on who controls or leads mental health services, research, or the alternatives to these. As everyone by now should be aware, recovery originated from the grassroots – people living with severe and enduring mental health conditions or distress who advocated for user-led, democratic and collective alternatives to medicine and professional dominance.

However, it is undisputable that mental health services remain controlled and led by professionals. On a concrete level, resources have not been redistributed to user-led alternatives. The National Survivor User Network’s 2019 Campaign, ‘The Value of User-led Groups’ highlights that many user-led alternatives struggle to survive with lack of funding, and often go under. Peer worker roles are becoming more prevalent but traditional power imbalances remain, with a lack of equality of pay, influence or career progression for peer workers and researchers. Ask yourselves, are peer workers paid as much as you? Or are they on zero-hours or temporary contracts?

Neorecovery pervades the ‘recovery’ research industry, just as it does clinical services. Where are the democratic, user-led studies on ‘recovery’ interventions or services? How many have the NIHR funded?

We couldn’t find any.

Randomised Controlled Trials and systematic reviews led by professionals, reporting on primary studies led by professionals, dominate hierarchies of evidence, and complex interventions proliferate and facilitate professorships. Yet, this is in direct contrast to the democratic nature of grassroots recovery and its stance that ‘recovery’ is an elusive phenomenon that evades, psychiatric, psychological and scientific language or measurement – it is an experience that cannot be quantified or manualised. We know what it is because we experience it. Listen to us.

So, what’s wrong with this departure?

It’s clear that the traditional power imbalances that grassroots recovery strongly opposed continue to exist:

Neorecovery services and research are based on psychological theories of attitude and behaviour change, as well as educational theories. They are not embedded in our theories or values, or those of grassroots recovery, which are collectivist and use the social model of disability. Democratic and collectivist services are virtually non-existent. Services are not emancipatory.

Neorecovery prioritises professional policy, and service driven aims and outcomes. These include discharge, ‘reducing dependency’; work as a health outcome and return on investment. These are not our outcomes or aims. Like grassroots recovery, we firmly believe that subjective experiences of ‘living well’ should be the primary outcome and concern of all mental health services. We will tell you when we are ‘living well’.

We talked earlier about how neorecovery distorts and misuses language. In neorecovery, recovery becomes an obligation, and sometimes an aggressively promoted demand from professionals. It’s the same old, paternalistic attitudes of ‘professional knows best’, but now couched in the language of empowerment and independence.

A significant consequence of neorecovery’s professional status quo, is the emergence of what Bridgit McWade calls ‘key figures’ and their spheres of influence. These key figures have access to “material and institutional power”. Their dominance, as she states, has led to the marginalisation of grassroots definitions of recovery and the exclusion of mad people. This material and institutional power is prominently seen in the various ‘recovery’ consultancy services on offer and in the recovery research industry:

The REFOCUS trial is the most widely known and cited Randomised Controlled Trial of a so-called recovery intervention. It received £2 million from the NIHR, but it was no more effective than usual care on all service user outcomes.

Let’s repeat that. The REFOCUS intervention was no more effective than usual care for service users.

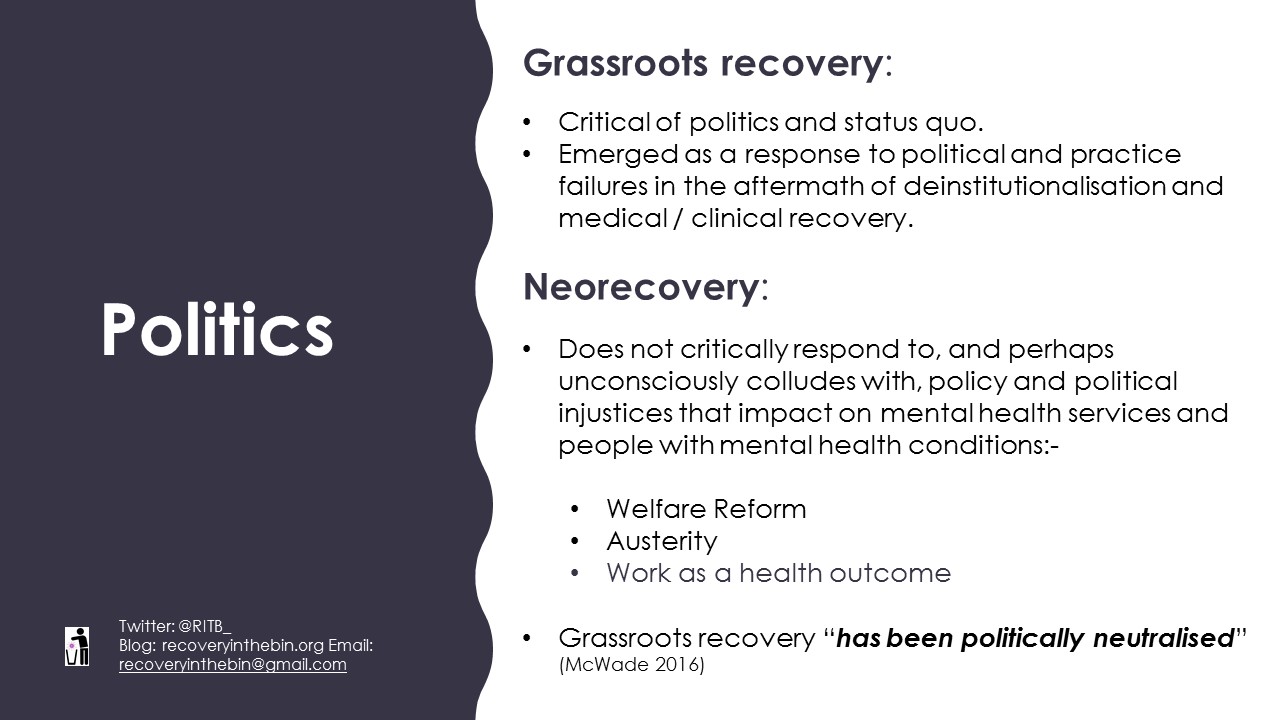

Differences in Political Bias

The final departure we will discuss today is neorecovery’s political bias. Whilst we have spoken about the influence of neoliberalism several times so far, we need to examine this feature in a bit more detail.

It’s important to remember that grassroots recovery, emerged as a critical response to political and practice failures in the aftermath of deinstitutionalisation and medical / clinical recovery. It was highly critical of social injustices inflicted by politics and policy which neglected people with long-term mental health conditions in the community. However, neorecovery does not critically respond to, and perhaps unconsciously colludes with, policy and political injustices that impact on mental health services and people with mental health conditions.

Welfare Reform and Austerity are some of the biggest political injustices of our time for people living with mental health conditions. Like recovery’s original grassroots proponents, we too are being neglected in the community by policy and politics.

Yet, Neorecovery’s silence is deafening.

So, what’s wrong with this departure?

As Bridgit McWade eloquently asserts, grassroots recovery ‘has been politically neutralised’ by the very institutions it sought to challenge.

We ARE the grassroots and neorecovery has neglected our calls for social justice and collectivist action.

Since recovery emerged in policy, key figures and influencers were quick to align their visions of social inclusion, and later ‘recovery’, to government policy. This alignment with neoliberal policy, particularly welfare to work and work as health outcome policies have continued. A current example of such complicity is the continued emphasis placed on our ‘right’ to work, above other ‘rights’, that are by far more important to us and in fact to non-mad people too!

This is not an isolated quote. Key influencers frequently promote the importance of work, often alongside neoliberal statements about ‘Making a contribution to society’ and portrayals of work as the most significant way of achieving personal fulfilment.

We ask this team of key influencers to reconsider their statement and continued emphasis on our right to work above all else in light of the mounting evidence from, amongst others, the Equality and Human Rights Commission, the United Nations Rapporteur on Adequate Housing, the United Nations Rapporteur on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the United Nations Rapporteur on Poverty, and the High Court Rulings that found people with mental health conditions are actively harmed by punitive welfare reform and its catalyst, austerity.

The Work Capability Assessment process has been associated with: 590 Suicides; 279,000 additional cases of self-reported mental health problems and 725,000 additional prescriptions for anti-depressants in areas where higher reassessments were reported. People with a mental health condition are 2.4 times more likely to lose their existing Disability Living Allowance entitlement when transferring to its replacement, Personal Independence Payment, compared to physical conditions.

The deaths of our peers, colleagues and allies continue to escalate through lack of appropriately resourced services under austerity and punitive, coercive and degrading welfare reform.

The number of people out of work is not OUR fundamental injustice.

Neorecovery’s Cumulative Impact

So, before we conclude, it’s worth reflecting on the cumulative impact Neorecovery’s key departures, which we have discussed today, have had on the original population for which recovery was intended – those with severe and enduring mental health conditions. Sweeping ‘recovery’ policies and interventions ‘for all’, which are underpinned by educational, attitude and behaviour change theories – in the context of neoliberal individualism and compulsory positivity – have meant that neorecovery caters for the norm, the socially acceptable and the majority who have mild to moderate difficulties.

This departure is confirmed by the endless redistribution of resources from inpatient and secondary care to primary care, and the prioritising of low intensity, short-term, low-cost ‘interventions’. The closure of wards and day centres in the name of recovery is commonplace and is rightly identified by Slade and others as an abuse of ‘recovery’. Where has the money for Recovery Colleges been taken from? Who is not getting a service now? Who’s needs are no longer being met?

Short-termism, low cost and standardised interventions for all, reflect neoliberal individualistic ideals of self-sufficiency and its mantras that ‘everything is within your reach if you just try hard enough’. This sets people with long-term psychosocial disabilities up for failure. These services and interventions mimic the prescriptive, linear, mechanistic process from A to B that grassroots recovery opposed because it does not afford flexibility for complex and long-term needs.

Grassroots recovery, including Deegan in 1988 and Anthony in 1993, actively advocated for a comprehensive community support system and an increase in long-term support. 18 years since recovery became policy in the UK and 31 years since Deegan spoke about her experiences. We’d like to ask:

Where are the long-term, flexible alternative services and support, based on collective values?

Where is the increased investment and comprehensive community support systems that Anthony spoke about?

Where are the democratic, truly user led services?

Conclusion

We can’t point to Victorian crumbling buildings to symbolise our confinement, ill-treatment and exclusion from society today. Neorecovery is much more insidious. Like grassroots recovery, our confinements, are ideological and politically sanctioned BUT they are hidden and illusive. Neorecovery promises to uplift and protect us, while simultaneously taking away our dignity, support and safeguards in the name of ‘independence’ – an independence we are not allowed to self-determine.

If material and institutional power remains with key professional figures, grassroots notions of recovery will forever be side-lined. Affording very little voice or room to those of us who are mad, and also mad about the way recovery has been co-opted, hijacked and distorted beyond recognition.

So, as mental health nurses and researchers, we ask that you stay true to the original recovery vision. Remember the grassroots, those of us with severe and enduring mental health conditions. Don’t abandon us to neorecovery. By the time Recovery Colleges are crumbling buildings, it will be too late.

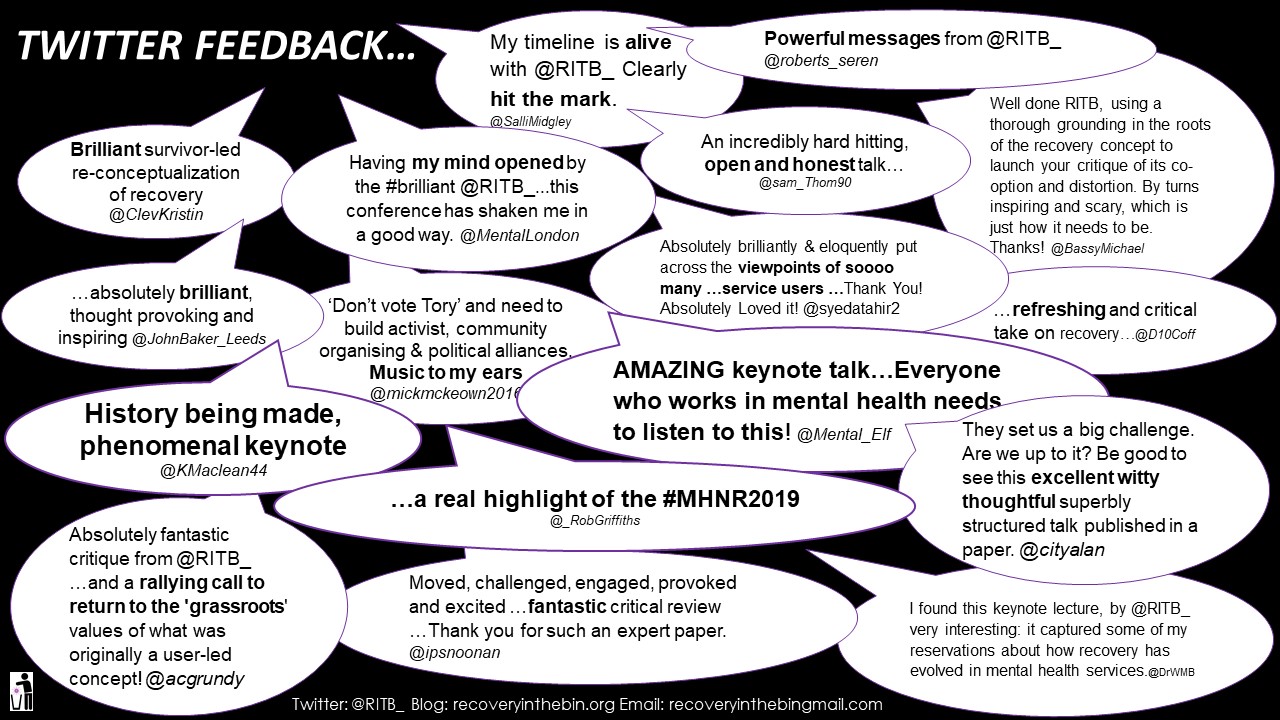

Twitter Feedback!

After the presentation we spoke exclusively to the Mental Elf! You can listen below:

References

(A PDF of the Keynote with inserted references will be made available separately).

Anonymous (1989) First Person Account: How I’ve managed chronic mental illness. Schizophrenia Bulletin 15:4.

Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11-23. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0095655.

Barr B., Taylor-Robinson D, Stuckler D, Loopstra R, Reeves A and Whitehead M. ‘First, do no harm’: Are disability assessments associated with adverse trends in mental health? A longitudinal ecological study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (2016) 70(4) 339-345 DOI: 10.1136/jech-2015-206209.

Bird V, Leamy M, Le Boutillier C, Williams J and Slade M (2014) REFOCUS (2nd edition): Promoting recovery in mental health services, London: Rethink Mental Illness.

Cummins, I. (2018) The Impact of Austerity on Mental Health Service Provision: A UK Perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2018, 15(6), 1145; https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061145.

Deegan, P. (1988) Recovery: The lived experience of rehabilitation (online). Available at: <https://www.nami.org/getattachment/Extranet/Education,-Training-and-Outreach-Programs/Signature-Classes/NAMI-Homefront/HF-Additional-Resources/HF15AR6LivedExpRehab.pdf> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Department of Health (2001a) Making it happen: A guide to delivering mental health promotion. London: DH.

Department of Health (2001b) The journey to recovery – The Government’s vision for mental health care. London: DH.

Disabilities Rights UK (2017) Your guide to the Care Act (online) Available at: <https://www.disabilityrightsuk.org/care-act-guide> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Edwards, B., M. (2015) Recovery: Accepting the unacceptable? Clinical Psychology Forum, 268, 26-27.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2018a) The cumulative impact on living standards of public spending changes. Manchester: Equalities and Human Rights Commission.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2018b) How well is the UK performing on disability rights? Manchester: Equalities and Human Rights Commission.

Equality and Human Rights Commission (2018c) The impact of welfare reform and welafae-to-work programmes. Manchester: Equalities and Human Rights Commission.

Foucault M. (1961) Madness and Civilisation: A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. London: Routledge Classics.

Guest (2012) Government silent over adviser’s Unum admission. Disability News Service, 2nd of February [Online]. Available at: <https://www.disabilitynewsservice.com/government-silent-over-advisers-unum-admission/> [Accessed 02.09.2019].

Hannigan, B., Simpson, A., Coffey, M., Barlow, S. and Jones, A. (2018) Care co-ordination as imagined, care coordination as done: findings from a cross-national mental health systems study. International Journal of Integrated Care 18 (3) article number 12 (10.5334/ijic.3978).

Houghton, J. F. (1982) First Person Account: Maintaining Mental Health in a Turbulent World. Schizophrenia Bulletin 8:3.

ImROC 2019 (online) Bespoke Consultancy (online) Available at: <http://imroc.wpengine.com/working-with-us/bespoke-consultancy/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M (2011) A conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis, British Journal of Psychiatry, 199, 445-452.

Mental Elf (2019) Twitter Profile (online) Available at: <https://twitter.com/Mental_Elf> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

McKeown, M., Wright, K. M. and Gadsby, J. (2018) The context and nature of mental health care in the 21st century. In K. M. Wright and M. McKeown (eds) Essentials of Mental Health Nursing. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

McWade, B. (2016) Recovery-as-Policy as a Form of Neoliberal State Making. Intersectionalities: A global journal of social work, analysis, research, policy and practice 5:3 pp 62 – 81.

MH v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions (PIP): [2016] UKUT 531 (AAC); [2018] AACR 12 (online) Available at: <https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5c3e1473e5274a70e95f35df/_2018__AACR_12ws.pdf> (Accessed 02.09.2019).

NSUN (2019) The value of user led groups campaign (online). Available at: <https://www.nsun.org.uk/faqs/the-value-of-user-led-groups-2019-campaign> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

O’Hara, M. (2010) The trouble with mental health treatment, The Guardian 10th of May [Online]. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/society/2010/aug/25/mental-health-treatment-rachel-perkins-mind [Accessed 02.09.2019].

O’Keefe, D., Sheridan, A., Kelly, A., Doyle, R., Madigans, K., Lawlor, E. and Clarke, M. (2018) ‘Recovery’ in the Real World: Service User Experiences of Mental Health Service Use and Recommendations for Change 20 Years on from a First Episode Psychosis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-018-0851-4.

Perkins, R., Repper, J., Rinaldi, M. and Brown, H. (2012) Recovery Colleges. ImROC Briefing Paper, Nottingham: ImROC https://imroc.org/resources/1-recovery-Colleges/.

Perkins, R. and Repper, J. (2017), “Editorial”, Mental Health and Social Inclusion, Vol. 21 No. 2, pp. 65-72. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-02-2017-0005.

Perkins, R., Meddings, S., Williams, S. and Repper, J. (2018) Recovery Colleges 10 Years On (online) Available at: <https://yavee1czwq2ianky1a2ws010-wpengine.netdna-ssl.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/ImROC-Recovery-Colleges-10-Years-On.pdf> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Pybus, K., Pickett, K. E., Prady, S. L., Lloyd, C., and Wilkinson, R. (2019) Discrediting experiences: outcomes of eligibility assessments for claimants with psychiatric compared with non-psychiatric conditions transferring to personal independence payments in England. British Journal of Psychiatry Open Vol 5:2 DOI: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.3

Price-Robertson, R., Obradovic, A. and Morgan, B. (2017) Relational recovery: beyond individualism in the recovery approach. Advances in Mental Health, Volume 15 (2) pp 108-120.

Recovery in the Bin (2016a) Unrecovery Star (online). Available at: <https://recoveryinthebin.org/unrecovery-star-2/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Recovery in the Bin (2016b) About (online). Available at: <https://recoveryinthebin.org/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Recovery in the Bin (2017) Stepford Recovery College Prospectus (online). Available at: <https://recoveryinthebin.org/2017/02/03/stepford-recovery-college/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Recovery in the Bin (2018a) Mental Health Peer Workers our Lived Experience – Part 1 (online). Available at: <https://recoveryinthebin.org/2018/11/07/mental-health-peer-workers-our-lived-experience-part-1/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Recovery in the Bin (2018b) Mental Health Peer Workers our Lived Experience – Part 2 (online). Available at: <https://recoveryinthebin.org/2018/11/09/mental-health-peer-workers-our-lived-experience-part-2/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Recovery in the Bin (2019) Neopaternalism – New wave paternalism in UK mental health services (online). Available at: <https://recoveryinthebin.org/2019/06/03/neopaternalism-new-wave-paternalism-in-uk-mental-health-services/> (Accessed 2.9.2019).

Rose, D. (2014) The mainstreaming of recovery. Journal of Mental Health 23:5 pp 217-218.

Roulstone, A. and Morgan, H. (2009) Neo-liberal Individualism or Self-Directed Support: Are we all speaking the same language on modernising adult social care? Social Policy and Society 8:3 pp 333-345.

Simpson, A., Hannigan, B., Coffey, M., Barlow, S., Cohen, R., Všetečková, J., Faulkner, A., Thornton, A. and Cartwright, M. (2016) Recovery-focused care planning and coordination in England and Wales: a cross-national mixed methods comparative case study. BMC Psychiatry 16(1), article number: 147. (10.1186/s12888-016-0858-x).

Slade M, Amering M, Farkas M, Hamilton B, O’Hagan M, Panther G, Perkins R, Shepherd G, Tse S, Whitley R (2014) Uses and abuses of recovery: implementing recovery-oriented practices in mental health systems. World Psychiatry, 13, 12-20.

Slade M, Bird V, Clarke E, Le Boutillier C, McCrone P, Macpherson R, Pesola F, Wallace G, Williams J, Leamy M (2015) Supporting recovery in patients with psychosis using adult mental health teams (REFOCUS): a multi-site cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry, 2, 503-514.

Taylor-Gooby P., Leruth B. (2018) Individualism and Neo-Liberalism. In: Taylor-Gooby P., Leruth B. (eds) Attitudes, Aspirations and Welfare. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham.

Spandler, H., Dellar, R. and Kemp, A. (2015) Foreword. In P. Sedgwick Psychopolitics. Unkant Publishers.

United Nations (2014) Report of the Special Rapporteur on adequate housing as a component of the right to an adequate standard of living, and on the right to non-discrimination in this context on her mission to the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (29 August–11 September 2013) [online] Available at: <https://www.ohchr.org/EN/HRBodies/HRC/RegularSessions/Session25/Documents/A_HRC_25_54_Add.2_ENG.DOC> [Accessed 02.09.2019]

United Nations (2017) Concluding observations on the initial report of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. [online] Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. Available at: http://docstore.ohchr.org/SelfServices/FilesHandler.ashx?enc=6QkG1d%2FPPRiCAqhKb7yhspCUnZhK1jU66fLQJyHIkqMIT3RDaLiqzhH8tVNxhro6S657eVNwuqlzu0xvsQUehREyYEQD%2BldQaLP31QDpRcmG35KYFtgGyAN%2BaB7cyky7 [Accessed 02.09.2019]

United Nations (2018) Statement on Visit to the United Kingdom, by Professor Philip Alston, United Nations Special Rapporteur on extreme poverty and human rights (online) Available at: https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/DisplayNews.aspx?NewsID=23881&LangID=E (Accessed 02.09.2019).

Woods, A., Hart, A. and Spandler, H. (2019) The Recovery Narrative: Politics and Possibilities of a Genre. Cult Med Psychiatry https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-019-09623-y.