By Dr. Jay Watts, Social Psychiatry, Queen Mary, University of London,

The forthcoming International Classiffication of Disease, 11th revision (ICD-11), includes a reconceptualisation of the categorisation of personality disorders with an explicitly expansionist objective. The ICD working group assumes this is a positive step, yet the grounds for this assumption are unclear.

Personality disorders will no longer be classified categorically, but rather using dimensions of severity— mild, moderate, or severe.1 An additional category of personality difficulty will be demarcated not as a disorder, but as the equivalent of a z-code in ICD-10—ie, a non- disease factor that affects health status and encounters with health services. Following assessment of severity, clinicians will then have the option of specifying one or more of five domain trait qualifiers: negative affectivity, anankastia, detachment, dissociality, and disinhibition. ICD-11 will include new guidance for personality disorders to be diagnosed during childhood, albeit with caution, as they had previously been “inappropriately set at late adolescence or early life adult life”[1]. Additionally, the revision will include a borderline pattern qualifier that is not dissimilar to the symptom profiles outlined in ICD-10 and the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder, 5th edition.

In their proposals, WHO are neglecting to incorporate progress in alternative approaches. The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology transdiagnostic system follows quantitative nosology to its logical conclusion, side-stepping construct validity problems by focusing on internalising, externalising, detachment, thought disorder, and somatisation, as they apply across the spectrum of psychiatric diseases [2]. The #TraumaNotPD movement reframes borderline as a form of complex trauma, evidenced not only by a robust literature connecting childhood trauma and the psychosocial environment with identity disturbance and interpersonal difficulties [3], but also patient testimonials supporting the benign face validity of such an approach.

With the publication of ICD-11, it is likely that more patients than before will be told they have a personality disorder. An explicit aim of the WHO remit for the ICD working group was to increase the diagnosis of personality disorder, on the basis that only around 8% of patients in the UK received this diagnosis, despite suggestions that prevalence of personality disorder is about 40–90% for inpatients and outpatients with psychiatric disorders [1]. The only eld study of ICD-11 diagnosis in practice looked at prevalence in 722 patients presenting with either health anxiety or anxiety and depressive disorders, or inpatients with psychiatric disorders. It showed not only that ICD-11 led to more patients being diagnosed with personality disorder (292 [40·4%] of 722) than did ICD-10 (244 [33·8%] of 722), but also that an additional 248 (34·3%) of the 722 patients were classified as having personality difficulties.2 Thus, 540 (74·8%) of 722 patients were diagnosed as having personality difficulty or disorder [4]. The assumption from WHO is that diagnosis using ICD-11 will prevent patients receiving treatments that they might not benefit from, introduce new treatments, and decrease the stigma that can be associated with personality disorders. However, no evidence as yet supports these assumptions.

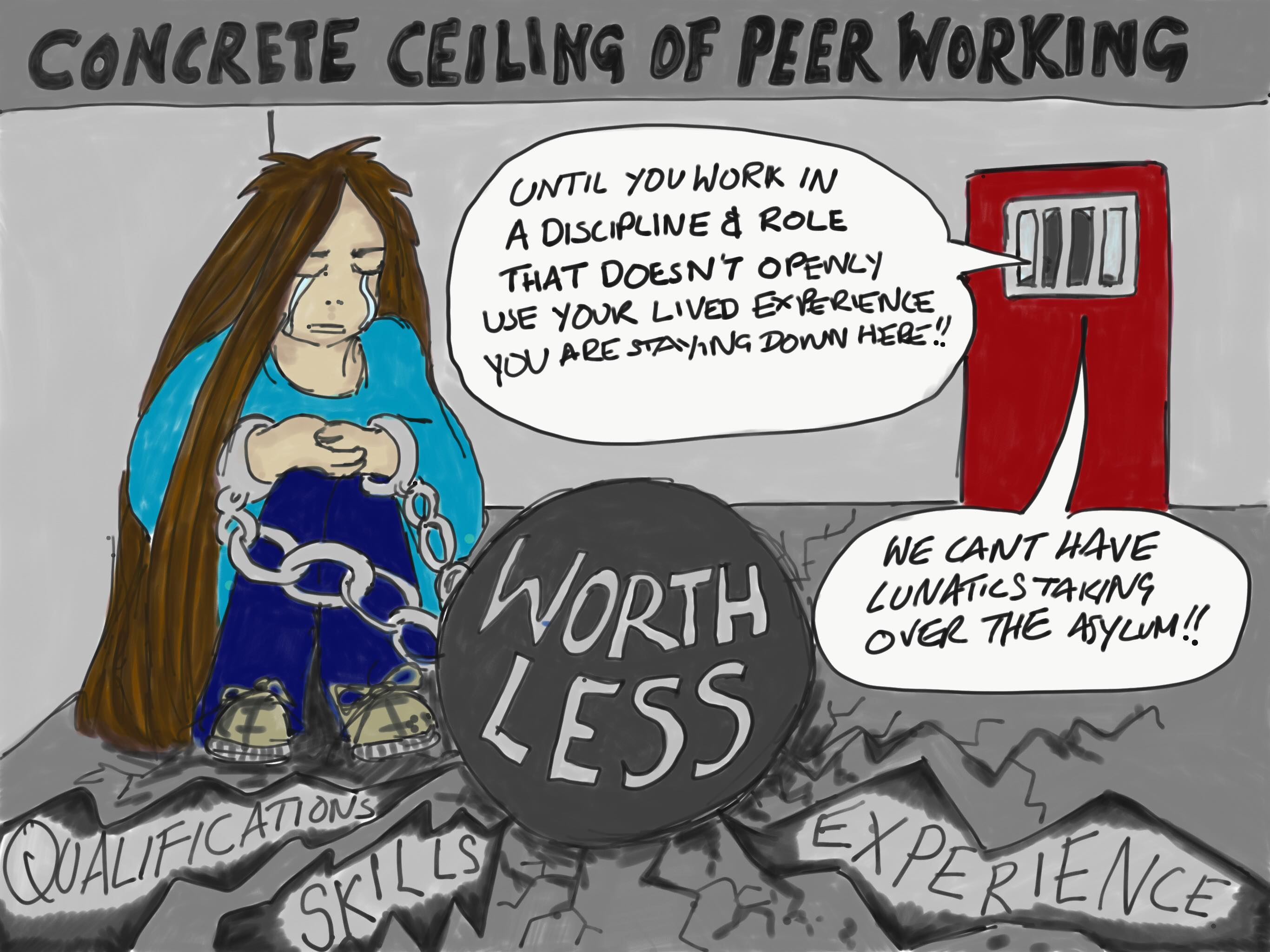

In a systematic review investigating personality disorder diagnosis and different clinical populations, a diagnosis often procured negative effects on identity and hope(similar to a diagnosis of psychosis) and did not provide functional utility (such as access to treatments) [5]. This is because the idea of a personality disorder often prejudices clinicians to situate symptoms of distress as manipulative, attention-seeking, and wilful6 and enables disdainful, neglectful, and sometimes even abusive responses that would be recognised as gross misconduct elsewhere in the mental health system, such as ignoring or disbelieving suicidal ideation [7].

The shaping effects of labelling someone as having personality disturbance or disorder appear to be entirely absent from consideration in the revision of the classification of personality disorder, with little or no consultation with service-user led organisations best placed to comment on real-world implications. Clinicians see treatment outcome less optimistically if they are told that someone has borderline personality disorder [8]. Patients have regularly reported that being diagnosed with a personality disorder is the ultimate character slur [9], leading to realisation of every worst fear one has had about themselves, and often reinforcing messages from abusers that they are inherently problematic [10]. To impose this discourse on even more patients, including adolescents, risks setting up a self-fulfilling prophecy by which expectations of a negative trajectory are established, and subsequently met.

Expansionism becomes more dangerous still when we consider that an explicit aim of the WHO working group was to develop a proposal that could be used in low-resource settings by people who are health workers with minimal professional training [1]. Encouraging such a cursory approach to personality diagnosis not only promotes negative thinking regarding differences in mental health and problematic norms, but also gives clinicians in severely overstretched services worldwide a ready signifier to block access to care to anyone who makes them uncomfortable, challenges them, or complains [11]. This will exacerbate discrimination against those from low-income settings, or with a poor education, who are more likely to meet diagnostic criteria for a personality disorder [12].

Borderline pattern has also been included in ICD-11. There is no scientific basis for inclusion, with “noticeable absence of evidence it’s a uni ed syndrome”, and overlap with mood, stress, and dissociation, rather than personality disorders [1]. Indeed “when an assessment was made of borderline features” in the modelling of personality traits “the domain structure seemed to disintegrate, and examining the full implications of this involved a great deal of the group’s time and early studies” [1]. Retention of borderline as a so-called hand- me-down diagnosis not only undermines the scientific claims of the new dimensional model, but also ensures that even patients who find diagnosis legitimising are disadvantaged, being coupled with a diagnosis that is openly contested.

Borderline has only been included in ICD-11 because of relentless campaigning from lobbyists, starting with a letter from the European Society for the Study of Personality Disorders in 2016, followed by campaigning from both the International and the North American Societies for the Study of Personality Disorders [1][13]. This led to a separate working group, though the Chair of the ICD-11 committee chose to exclude himself [1], having written “nothing about it is driven by personality. The very name borderline personality disorder betrays an abrogation of diagnosis” [14]. The discourse from WHO is that the pragmatic compromise of including a borderline pattern to assuage these lobbyists is now unanimous [1]. Unanimous for whom? Certainly not patients, the majority of whom are traumatised women who remain largely unheard and ideologically restricted (coshed) by this most misogynistic of classifications [7] and who cannot take refuge in a narrowly de ned new diagnosis of complex post-traumatic stress disorder, as so many had hoped.

1 Tyrer P, Mulder R, Kim YR, Crawford MJ. The development of the ICD-11 classiffication of personality disorders. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2019; published online Jan 2. DOI:10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050718-095736.

2 Kotov R, Krueger RF, Watson D,et al. The hierarchical taxonomy of psychopathology (HiTOP): a dimensional alternative to traditional nosologies. J Abnorm Psychol 2017; 126: 454–77.

3 Giourou E, Skokou M, Andrew SP, Alexopoulou K, Gourzis P, Jelastopulu E. Complex posttraumatic stress disorder: the need to consolidate a distinct clinical syndrome or to reevaluate features of psychiatric disorders following interpersonal trauma? World J Psychiatry 2018; 8: 12–19.

4 Tyrer P, Crawford M, Sanatinia R, et al. Preliminary studies of the ICD-11 classiffcation of personality disorder in practice. Personal Ment Health 2014; 8: 254–63.

5 Perkins A, Ridler J, Browes D, Peryer G, Notley C, Hackmann C. Experiencing mental health diagnosis: a systematic review of service user, clinician, and carer perspectives across clinical settings. Lancet Psychiatry 2018; 5: 747–64.

6 Black DW, Blum N, Pfohl B, et al. Attitudes toward borderline personality disorder: a survey of 706 mental health clinicians. CNS Spectr 2011; 16: 67–74.

7 Phillips S, Stafford P, Turner K. Personality disorder in the bin. 2017. http://aspd-incontext.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/PDintheBin- London-PS-KJT-3.5.17-1.pdf (accessed March 28, 2019).

8 Lam DC, Poplavskaya EV, Salkovskis PM, Hogg LI, Panting H. An experimental investigation of the impact of personality disorder diagnosis on clinicians: can we see past the borderline? Behav Cogn Psychother 2016; 44: 361–73.

9 Shaw C. The most savage insult. Equilibrium Magazine 2012; 46: 23–26.

10 Gary H. A diagnosis of ‘borderline personality disorder’. Who am I? Who could I have been? Who can I become? Psychosis: Psychological, Social and Integrative Approaches 2018; 10: 70–75.

11 Recovery in the bin. A simple guide to avoid receiving a diagnosis of ‘Personality Disorder’. Clinical Psychology Forum 2016; 279: 13–16.

12 Coid J, Yang M, Tyrer P, Roberts A, Ullrich S. Prevalence and correlates of personality disorder in Great Britain. Br J Psychiatry 2006; 188: 423–31.

13 Reed GM. Progress in developing a classiffication of personality disorders for ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2018; 17: 227–29.

14 Tyrer P. Borderline personality disorder and mood. Br J Psychiatry 2014; 205: 161–62.

First Published in The Lancet

Recovery In The Bin (RITB) is covered by a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License